The History Column: Moonshine

Radar jammers often include pulse repeater modes. Modern systems may use a digital RF memory (DRFM), which digitizes incoming pulses, allowing them to be retransmitted multiple times with different time delays, amplitudes and Doppler signatures. However, the concept of pulse repeater jamming is not new and such techniques were first used in the UK in WW2, using an airborne equipment called Moonshine [1] fitted on Boulton Paul Defiant aircraft (Fig.1).

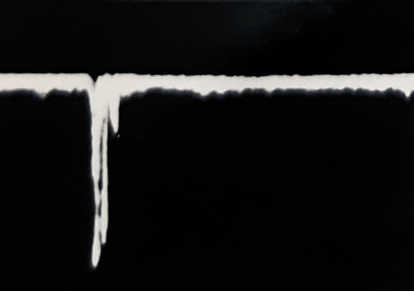

Moonshine was designed to deceive the ground-based German Freya radars, each operating on a spot frequency in the band 120 – 128 MHz, that provided early warning of air attack. The aim was to spoof the Freya reporting system into believing that a large number of aircraft were approaching. A radar pulse received by Moonshine triggered a low power pulse transmitter on approximately the same frequency. The pulses were amplitude modulated to simulate the breathing and interweaving nature that was characteristic of extended returns from a number of close-flying aircraft. Fig.2 compares an “A-scope” Moonshine signal with a real signature from a flight of 30 Spitfire aircraft. Typically, six to eight aircraft, each carrying a Moonshine set tuned to a different frequency, were required to cover the whole band used by Freya.

The first operation occurred in July 1942 and was extremely successful. Three fighters fitted with Moonshine caused the entire enemy fighter force in the Cherbourg area to become airborne. The use of this spoof squadron continued for the remainder of 1942. However, eventually, the frequency band used by the Freya radars was increased to the extent that Moonshine was no longer practicable in that role.

In 1944 the Moonshine technique was adapted for naval use, to spoof the German airborne maritime reconnaissance aircraft, particularly the Fug 200 Hohentwiel [2], which operated in the band 540-590 MHz (55 cm wavelength). The original Moonshine equipment now employed an operator to listen for radar signals of interest and tune the set to the required frequency. This version of Moonshine provided decoy signals during operations Taxable and Glimmer [3], in support of Operation Overlord on 6th June 1944 (D-Day).

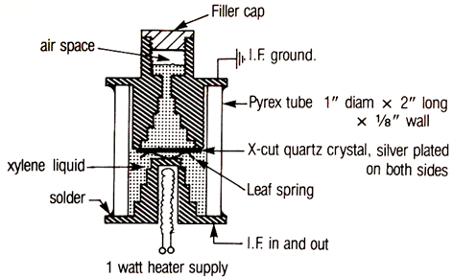

These systems did not actually repeat a received pulse but triggered independent pulses on the same frequency. The first true repeater jammers were a US version of Moonshine, AN/APQ-15 [4], that was developed by ITT in 1944/45. It had interchangeable RF heads to cover 88-110, 107-134 and 130-162 MHz, with an IF frequency of 15 MHz having a 5 MHz bandwidth. It had a maximum transmitter power of 1W for an input of 2.5 mV. A modulated crystal delay line was used to create the false returns. The incoming signal was mixed down to IF and then used to excite two crystal delay cells, tuned for about 13 and 16 MHz respectively. The quartz crystal in each cell (see Fig.3) launched waves into a liquid, xylene, which had a propagation velocity of about 1 s per mm. There were reflecting edges along the cell over about 25 mm (1 inch) either side of the crystal, which produced delayed reflections lasting up to 50 s. The increasing attenuation with delay through the liquid was compensated in the following IF amplification stages before mixing up for retransmission. The “breathing” action of the decoy response was created by local heating under the cells. This was reported to be very realistic.

Moonshine was the first of a long line of active radar deception jammers, that continue to the present day.

REFERENCES

[1] Moonshine, TRE Report T1285, 5/R/71/JH, 1 October 1942 (UK National Archives AVIA 26/287)

[2] S. Watts, "The FuG 200 Hohentwiel Airborne Maritime Surveillance Radar," IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 28-37, 1 Feb. 2021.

[3] H. Griffiths, "The D-Day deception operations TAXABLE and GLIMMER", IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 12-20, March 2015.

[4] S. Dodington, The Development of “Moonshine” in the US in World War II, in “Radar Development to 1945”, ed. R. Burns, Peter Peregrinus, 1988, pp. 410-415

Authored by Simon Watts

University College London